L’Institut Français d’Ecosse, Edinburgh Fringe Festival; 10th August 2014

In the gloom of a rainy Scottish evening, the glowing tent on the green outside L’Institut Français d’Ecosse is a welcome beacon. Inside, Belgian company T1J (Theatre d’Un Jour) are ready to draw us into their earthy fantasy of the mind in L’Enfant Qui…, an acrobatic exploration of childhood hallucination, based upon the life and work of sculptor Jephan de Villiers.

In the gloom of a rainy Scottish evening, the glowing tent on the green outside L’Institut Français d’Ecosse is a welcome beacon. Inside, Belgian company T1J (Theatre d’Un Jour) are ready to draw us into their earthy fantasy of the mind in L’Enfant Qui…, an acrobatic exploration of childhood hallucination, based upon the life and work of sculptor Jephan de Villiers.

The central character of the young De Villiers is played by an exquisite puppet, created by Polina Borisova and expertly animated by Morgane Aimerie Robin, whose polished wooden face seems to shift expression in the light, softly smiling, serious or afraid. The rest of the troupe is comprised of acrobatic flyer Caroline LeRoy, twin bases of Michaël Pallandre and Adrià Cordoncillo, and cellist Florence Sauveur, who even finds herself transported through the air at one point.

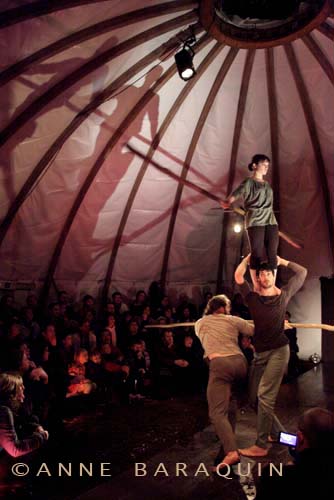

Beginning with the boy’s fascination for the natural world, the purposely constructed tent is supported by unbroken curves of wood, and carpeted in rich brown earth. Fallen leaves are strewn around, and a large tree stump sits in the centre of the ring, on the smooth wooden pathway that stretches across the floor. Stage lights are embedded within short posts around the circle, that are not quite so organic, but neither too incongruous, and our wooden bench seats are lit with romantic miniature chandeliers.

Beginning with the boy’s fascination for the natural world, the purposely constructed tent is supported by unbroken curves of wood, and carpeted in rich brown earth. Fallen leaves are strewn around, and a large tree stump sits in the centre of the ring, on the smooth wooden pathway that stretches across the floor. Stage lights are embedded within short posts around the circle, that are not quite so organic, but neither too incongruous, and our wooden bench seats are lit with romantic miniature chandeliers.

An introductory speech from Artistic Director Patrick Masset reveals the genesis of the piece, and the style in which De Villiers works. The floor is swept. The show begins.

For all it’s charm and rustic autumnal beauty, L’Enfant Qui… is a show that repeatedly reminds us of the dangers that could shatter our tranquility at any moment. Axes are pointed at us, polished tree branches swung until we feel they must come hurtling at us. There is no security in this world. As the boy experiences the attraction and terror of his hallucinations, brought to life by the clambering LeRoy, Pallandre and Cordoncillo, and the acoustic bowing of the cello, he solemnly takes all the strangeness in his stride, as children are wont to do. When you’re learning what the world is, everything is strange; everything is normal.

He is a curious child, and we first meet him exploring the woods, stepping off the safety of the rope path laid out for him. He is a sweet child, bespectacled and duffle-coated, offering the natural treasures he finds to members of the audience, redistributing – reshaping – the wealth of his environment.

At first the figures of his delusion float gently by, LeRoy treading a rope that slides from under her, or climbing the spiral staircase of a smoothed tree-branch pole via the hands of Pallandre and Cordoncillo. As the boy – and we – are seduced by their dreamy quality, they begin to darken. The boy’s own form begins to morph with that of his puppeteer as they sit cross-legged together. He is torn from her comforting control, a mind torn from it’s anchors, as the pitching, threatening acrobatic visions build in intensity.

At first the figures of his delusion float gently by, LeRoy treading a rope that slides from under her, or climbing the spiral staircase of a smoothed tree-branch pole via the hands of Pallandre and Cordoncillo. As the boy – and we – are seduced by their dreamy quality, they begin to darken. The boy’s own form begins to morph with that of his puppeteer as they sit cross-legged together. He is torn from her comforting control, a mind torn from it’s anchors, as the pitching, threatening acrobatic visions build in intensity.

An effortlessly quick and smooth 3-high tower dissolves as the episode fades. We see a shadowy projection of the winged figure from De Villier’s Mille et Trois Souffles d’Écorce ou La Derniere Forêt en Marche, and then the four actors appear, masked in the style of his wooden idols, bearing candle lit altars to place around the circle.

As they rotate around the four points, I understand just enough of their French to grasp Robin is telling us about her childhood, that LeRoy had a dog who ate the guinea pig, and she wept and wept, that Cordoncillo is singing to the wistful melody of Puff The Magic Dragon. I enjoy the disjointed and tenuous understanding, fitting in this world of uncertainties.

As they rotate around the four points, I understand just enough of their French to grasp Robin is telling us about her childhood, that LeRoy had a dog who ate the guinea pig, and she wept and wept, that Cordoncillo is singing to the wistful melody of Puff The Magic Dragon. I enjoy the disjointed and tenuous understanding, fitting in this world of uncertainties.

Without my noticing, the roof has been hung with floor to ceiling branches, dangling at intervals around the circle. Sauveur emerges from the shadows with her cello, accompanied by Cordoncillo on saxophone, and distorted hand-balance from LeRoy and Pallandre. A distinctive single-handed pose is a repeat from earlier, and I wonder if it is referential of another of De Villier’s sculpted figures.

There is an essential surrealism to L’Enfant Qui…, but it is of an enticing, captivating kind. The boy leaves carved offerings to his personal spirits from a hand-drawn cart straight out of De Villier’s canon, and they multiply. These spirits have a life of their own, seemingly beyond him. As his body slowly turns to forest and madness, the performance ends, as suddenly as a dream.

Organic through and through, L’Enfant Qui… takes highly skilled acrobatics into unusual and pertinent choreographies, with an edge of mortality circling at the threshold. Patrick Masset’s working methods, with the artists who join his 19 year old T1J, are ‘to provide a universe in which they find their own way, little by little’, working responsively to his performers and the material. This is a haunting work that has stuck with me, my mind returning to it again and again.