This review is based on a pre-print version of the book. Some page numbers may differ in the eventual publication.

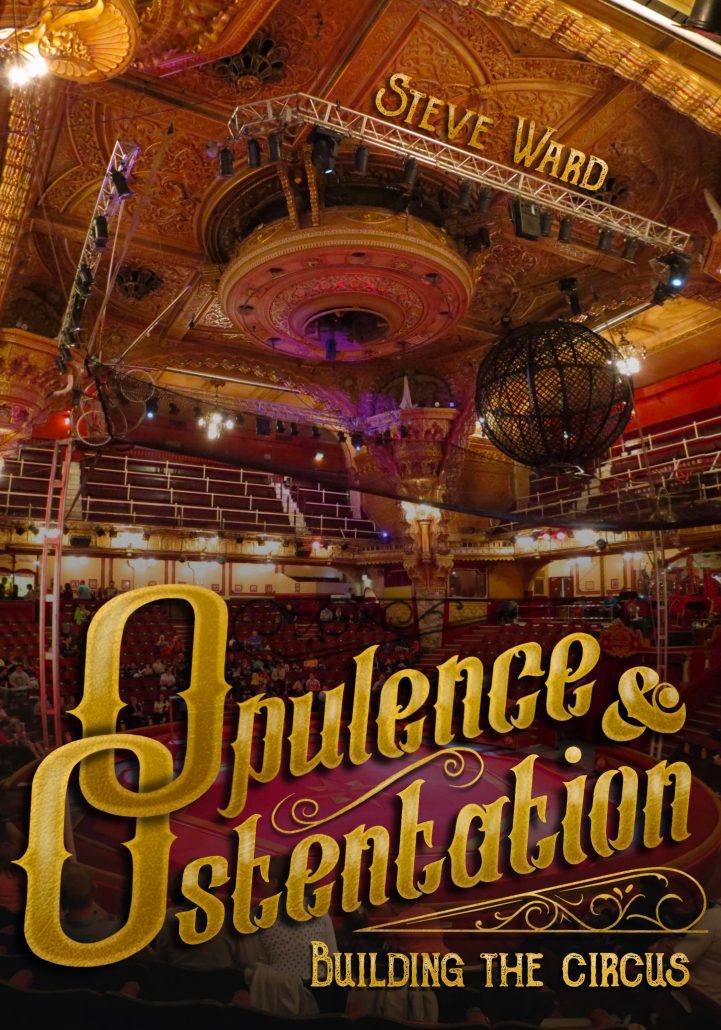

Circus teacher-turned-historian Steve Ward adds another volume to his collection of published works, which have earned him a doctorate from the University of Hull. This time, the focus moves away from people involved with circus activity, to the buildings in which circus is – and has been – performed over time.

Extensive historical sources are quoted in length, describing various buildings in great detail, from their structure to their decor. It’s interesting both that such public records are available and that the details they focus on are often clear indicators of different public concerns over time. Newspapers today do not describe new constructions in any way, as far as I am aware, and I’m sure that if they did the focus would rarely touch on their susceptibility to fire and potential escape routes, for example!

The structure of the book loosely follows the journey of the institutionalised circus that stems from the developments of Philip Astley: from London outwards to the rest of the British Isles, to France, to the various other quarters of Europe and the former Soviet states, and then to the continents of North America and Australasia. Discussions of Asian, South American and African circus histories are conspicuously absent, however attention to these regions may be – as the introductory material suggests – better suited to a further volume to avoid the trap of becoming too dense. Ward does a sterling job of constructing the narrative links between his historical sources in an engaging way but, as I don’t hold a specialist interest in this subject, the nature of so much building history begins to feels rather repetitive to me and the 220 page length of the book (before notes and references etc) feels right for my attention span and focus.

Reading this book pulls my attention to the evolving nature of how we understand history. Each successive scholar builds on the last, so that what was once ‘knowledge’ becomes myth to be overturned. Ward is at the front of the curve, making valuable points in the wake of Britain’s 2018 celebrations of Philip Astley as ‘the founder of Modern circus’:

Contrary to popular Astleian mythology, Astley did not immediately fill his venue with jugglers and acrobats and thereby create the ‘circus’. This formative move was first made in September 1768 by Astley’s rivals, the Woltons who were performing at the nearby Dog and Duck Inn. In association with a Mr. Wilkinson and pupils at a fund-raising show in aid of a burnt-out property in Southwark, their demonstrations of horsemanship were interspersed with tumbling, rope-dancing, and pistol shooting. Astley was soon to copy this idea for his Christmas entertainments by including tumbling and an equestrian monkey.

(p.25-26)

Where Astley did take a lead, however, was in the repeat construction of circus buildings further afield from his initial venture. Ward presents his extensive research in a cohesive and readable manner, detailing trends in construction materials, and in building shape, size and function, across time and national borders. A chapter on Charles Hengler (né Frederick) reveals how his construction work and legacy of specialised performance spaces began ‘to separate the circus as a distinct art form from the theatre’ (p.54) in the UK. A further two chapters remain focused within the British Isles (Ward’s primary speciality), before a chapter devoted to French developments, (which inspired other European cities to follow suit), two additional chapters on Europe, one chapter on Imperial Russia and the former Soviet states, and one chapter on overseas developments in North America and Australasia. A final chapter looks to the future, with some discussion of contemporary circus buildings. To my mind there is a missed opportunity here to draw connections between the recent practice of presenting touring circus performance within Spiegeltents, echoing the movable wooden circus constructions of the past, and there are also some prominent spaces constructed for and used by contemporary circus organisations that don’t yet receive a mention.

Nonetheless, the thread that Ward draws between the architectures of the past and the present – and particularly how building designs relate both to performance and audiencing practices – is an invaluable contribution to circus scholarship. The material legacies that circus has left to the world are often overlooked out of interest in more intangible cultural impacts. This book goes some way to highlight, however, that these are inextricably interwoven.

Ward also raises a fascinating question for further study: what is the optimal balance of intimacy and spectacle that circus audiences desire? His observations of shifting sizes of circus buildings in different periods offers a new angle on historical evidence for scholars of circus audiences to delve into.