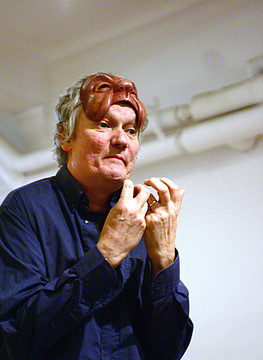

Mick Barnfather is a theatre director, actor and teacher with over 35 years of professional industry experience. Renowned for his exploratory clown workshops, Mick is well-versed in making people laugh. Here he explains more about this skilful, yet widely misconceived art form…

Over your career you’ve worked on a number of successful television, stage and radio productions, as both an actor and a director. How did you first come to be involved in the performing arts, and how did you find your way into clowning?

Mick: I think I’ve always been interested in clown, but I perhaps didn’t know that I was. I’ve always liked mucking around and playing. I’ve got some pretty ridiculous friends, and I suppose you gravitate towards people who have a similar sense of humour, or intellect, or whatever. I’m not intellectual, but I’ve always enjoyed joking around. And it was many years ago now, maybe 40 years or so, that I first saw a mime act in the streets of Paris and decided that I wanted to do that. So I went to a mime school – Desmond Jones – and someone came in and did some mask work, and then someone came in and did some clown work and I just fell in love with it. It seemed to really suit me, and it was something I seemed to do well in, whereas in the end I found the mime somewhat limiting and, ultimately for me, a little bit boring.

So you found a sort of freedom in clown work compared to other types of performance?

Mick: Absolutely. I found it allowed me to express myself a bit more, and I had success in it. And I then started to become really fascinated by what it is that makes people laugh.

And what is it that makes people laugh?

Mick: There’s a really big moment of laughter in all comedies. There’s that moment of dilemma when people get caught out. If you think of all sit-coms for example, however good or bad they are, whether they’re played well or not, what tends to be at the heart of them is people making mistakes and being embarrassed – people being caught out.

Like Fawlty Towers?

Mick: Certainly, Fawlty Towers is a wonderful example, because John Cleese is constantly being caught out, either by a guest looking at him and him then realising that he’s been spotted, or by his wife Cybil coming in and shouting ‘Basil!’ I feel that’s the big moment in clown as well. Clowns moves from one disaster to the next, seemingly solving one problem only to create another. And it’s so beautiful to see people with a problem. Now, having said that, in life if someone is having a hard time it’s not so nice because it’s real. But in comedy and theatre it’s not real and it’s very evident that the performer is playing, and that’s why we’re invited to laugh. We’re invited to laugh at our own fragility.

In life we try to avoid being the butt of a joke. We go to a job interview for example and we want to present ourselves really well. We don’t want to be the one who gets up, goes to walk out and gets their foot caught in their chair and then walks out the wrong door and into the broom cupboard instead of the exit door. We don’t want to be that person. But in theatre we love to laugh at that because often that sort of thing does happen to people. It’s a real paradox, I find, that those things that do happen – and that you wish weren’t happening at the time – one hour later are your best stories. And how boring we would be if those things didn’t happen? So I guess there’s that element to humour, that we like to laugh at those things and they inspire our comic writing.

You’ve been teaching clown at the National Centre for Circus Arts for many years now, and there’s often a lot of noise and movement involved in your classes. Can you talk me through a typical session?

Mick: I suppose my structure of a class is first of all waking people up with a little bit of a tag game and a lot of play – because ultimately theatre is play, so it has to be very playful – and then I look for more concentrated exercises where people start to communicate more with each other on a level of playfulness. I quite often then look to play games where people are caught out. It’s important with clowning to get people comfortable with that moment in a sort of invisible way through games. And most of my games are designed in such a way that you will get caught out. For example, I’ll devise a rhythm exercise but I won’t teach it proficiently enough for the students to actually get it, and then I’ll ask four or five of them to present it to an audience straight away, that kind of thing. It’s all about helping the student to embrace that moment of dilemma. After the games I move on to some simple clowning exercises and then make them a little more complicated. And it’s the same basic rule – you’re always looking for the game and the pleasure to be caught out.

So you set people up for failure?

Mick: Yeah, it’s about setting them up and then seeing how they react: are they embarrassed when they make a mistake? Do they say sorry? Or do they embrace it? With clown you have to embrace it. Your reaction in that moment is real if you’re enjoying the game, and it’s exactly that that you must then take into the performance. When you play those moments or a gag night after night it should look as if it’s the first time it has happened to you, if not an audience won’t laugh.

Asked to describe a clown, many people would conjure a Ronald McDonald type figure with frizzy hair, baggy dungarees and ridiculous over-sized shoes. Can you explain what clowning really is?

Mick: People always ask, ‘What is Clown?’ and I just tell them in one simple little sentence that it’s the fun and the joy to be stupid, and to make that stupidity accessible to your audience. That is clown – it has to be fun. If you have the fun to be stupid then potentially theatre is for you. If you don’t have the fun to be stupid, if you’re forcing stupidity, then the psychiatrist is the place for you. That’s one of my little introductory things. And then, again, when I talk about stupidity, I give a little government health warning and say, don’t be any more stupid than you already are because nature’s made you stupid enough, meaning that we have to believe that you are that stupid, and that only comes from your fun to be stupid. If you start pretending you’re a bit of an idiot then it just won’t work and we’ll see right through you.

So it’s about unlocking the individual’s inner stupidity?

Mick: Yes, it’s absolutely about yourself – there’s no acting required. And if you just remain yourself then little by little you’ll start to listen with an intuitive ear when people are laughing at you and, just as importantly, when they’re not. This then shapes and reveals your comic persona, which is not a character but you. When you find someone like Tommy Cooper or Eric Morecambe, I never look at them and think they’re just playing a character; they’re very much themselves and having fun to be daft. For example, Eric Morecambe when he did those plays with Ernie Wise where he would dress up as a centurion or some other character from history, he was playing a character, but he was always himself doing it. He was never any different, whatever the costume he put on – he was always that daft person. And for me that is very much the clown. You can put any costume on, but it’s always the same idiot underneath. The clown is always you.

You also teach clown workshops outside of the National Centre. Are these for professionals or beginners, or both?

Mick: I get a lot of professionals – and it doesn’t mean to say that they’re good – and I get a lot of beginners as well – and it doesn’t mean to say that they’re bad. With clown, or any of these subjects, the first day is all about me relaying what I’m looking for, and explaining my approach. I take people very gently from one step into the next and into the next. You can’t jump straight in because some people have no idea, and some people have their own idea of what clowning is, so you’ve got to get rid of all of that first and explain that they won’t be doing an impersonation of Coco the Clown. I play a few games and ask people to think about what made us laugh and then we all come to agree that, yes, it was the moment that person got caught out and their reaction. So I do it very much through game and then little by little we start going into clown, so really the workshops are suitable for all levels of experience.

What would you say are the benefits of learning to clown?

Mick: I guess it depends on what you come in looking for. My workshops aren’t really designed for personal development. I like people who come in and want to learn about clowning and want to find out how ridiculous they are. For an actor, potentially it could help them find another side to themselves. With clown it’s so out to the audience that I think it’s a very good thing for actors just to be themselves – drop the act and just be yourself and see whether you can just simply communicate with people. If you find you have a talent for it, you know, whatever talent you have will always go into the work that you do. If you can gain skills in comedy, tragedy and everything else then you’re really lucky because you’re not going to get pinned in a box and your work is going to get so much more interesting. And I think that for someone who’s interested in clown and has done none before, they’ll get a chance to think about whether it’s something they’d pursue, whilst also having a good time. A clown workshop is intense but you do have a very good laugh. And you see some very inspiring things.

What would you say are the most enjoyable and challenging aspects to your work?

Mick: Teaching I enjoy. It’s lovely to work with young people, people who have a dream, people who are enthusiastic. I love enthusiasm. I’m sometimes just amazed by the talent of some of these kids at 19, 20, 21. It’s sometimes quite phenomenal. So for me that’s the real enjoyment. With directing, I always enjoy a rehearsal, and it’s very inspiring to work with good actors and good performers. That is very inspiring. People’s talent, you know, wow! And what they give when they’re in the space. Sometimes you just look at them and think wow! And everybody’s so different. It’s never the same thing because everybody is so unique. I suppose the challenge is bringing that uniqueness out of people. And part of the challenge with teaching, having done it for such a long time, is keeping it fresh, trying to reinvent all the time with new games and exercises to really unlock people’s talent.

Finally, if you could offer one piece of advice to someone embarking on a career in clown, comedy or theatre what would it be?

Mick: I think with clown it’s important to always be open. And with theatre too – always be open. Don’t become one of those actors who won’t try things. Don’t be one of those performers who thinks their character wouldn’t do this or that, or who won’t do exploratory work. Be open. Always be looking to broaden your vocabulary. It starts to get like any other job otherwise. I mean, performance is a job, but it’s a very special one. You have to fight against closing up and thinking you know everything. Always be open to learning.